Your Wikipedia entry says you are “an architect and scholar who conducts activities of teaching, criticism and research.” Which term represents you best?

Am I really in Wikipedia? I didn’t know. I am first of all a college professor. All the rest of these activities are done to offer my students original, contemporary contents for research. This does not mean that I work on publications, books or other things because I have portions of free time to consume. But the heart of my work is teaching. Everything else is a way to continue to be informed, to continue to bring my students original materials.

Last year you brought exhibitions into Euroluce, also with some important art pieces. What is the borderline, in your view, that separates art from design?

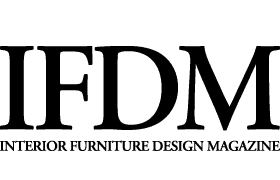

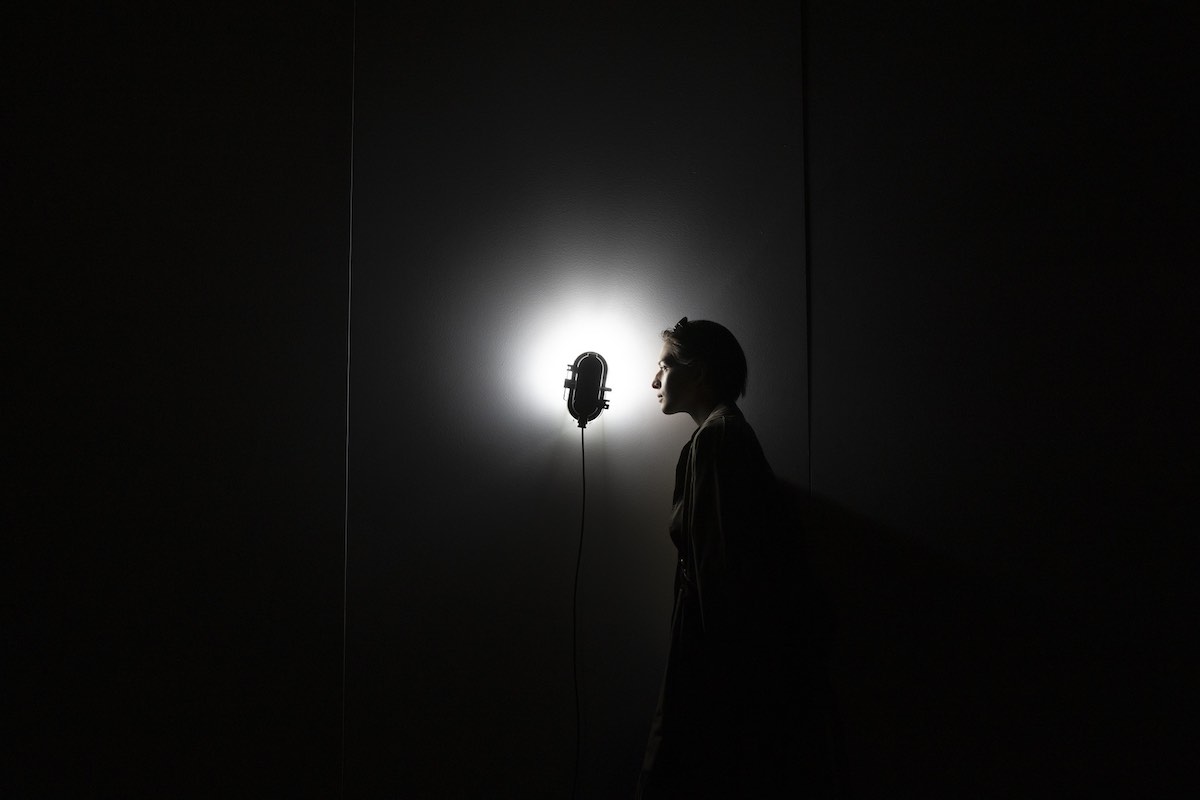

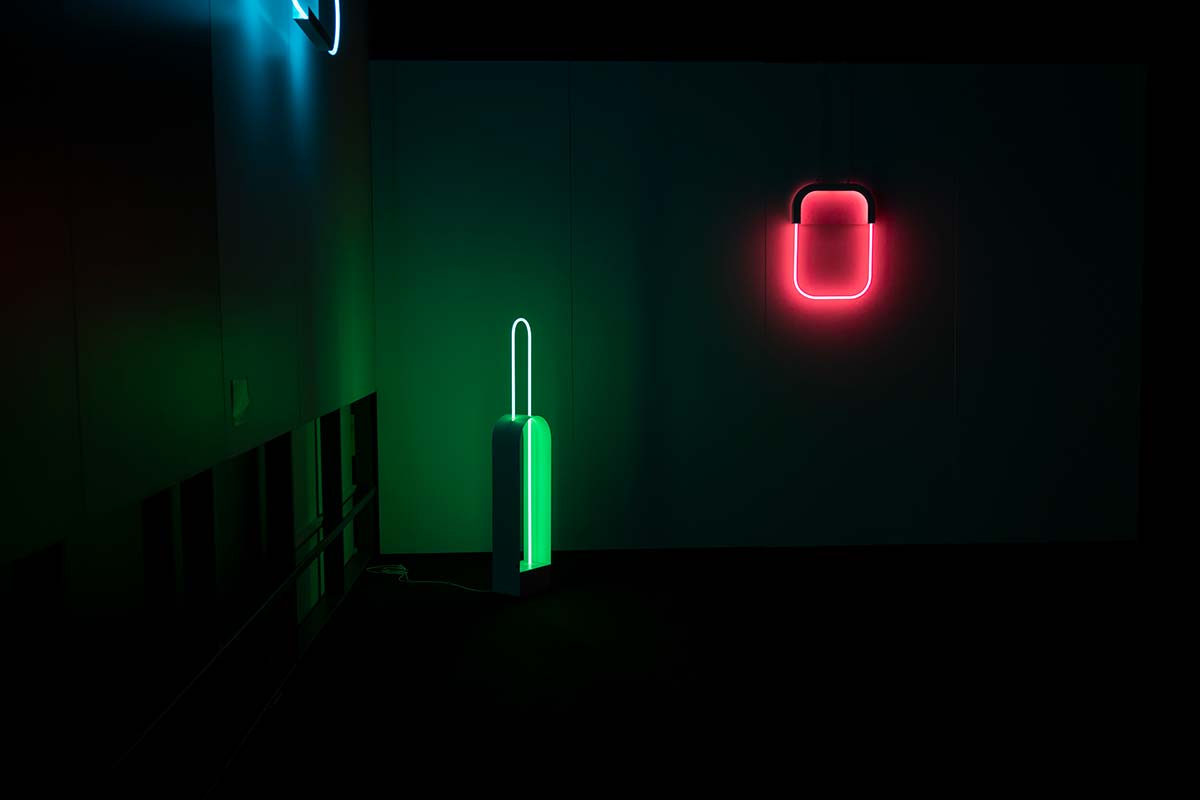

In the past everything was relatively simple in theoretical terms: art had to make us think, to provoke us and amaze us. Design, on the other hand, had to perform a function. Two different disciplines, though certainly interrelated. But from Meret Oppenheim onward (the artist who in 1939 designed the Traccia table, an oval top on two bird legs, now in the Cassina catalogue, ed.) things became a bit more complex, the boundary began to get blurred and confused at times, and many short circuits began to happen. Italian history has been made by creators who by nature were crossovers, personalities that cannot be limited to architecture, writing, photography: Munari, Balla, Depero, Mendini, Getulio Alviani, Corrado Levi, Ugo La Pietra, Nanda Vigo… For them, that borderline does not exist. Then things got even more mixed up: just consider the beautiful lamps by Michael Anastassiades, the greatest innovator of recent years: had it not been for the acceptance that brought an artist like Cerith Wyn Evans into the world of lighting, he might not have been able to make them. Or Daniel Rybakken, who showed up at the Salone Satellite with a white panel having a un parallelogram of LEDs on the back, suggesting the way light enters from a window: a project that links back to the work of Olafur Eliasson, Robert Irwin or James Turrell. For Euroluce we started with the new layout created by Lombardini22, a project of urbanism, in a certain sense. I thought about historical cities, full of art, where something happens at every turn, and I proposed doing the same thing, bringing into these renewed pavilions happenings that would be capable of capturing attention, making them more multidisciplinary, multicentric. The presence of various disciplines was intentional: architecture, pure art, art + design, more experimental works, photography at the highest level. If we had had more time, I would have brought others still: graphic design, illustration. Disciplines that have always fed on each other, but have normally not entered the Salone.

You are also a curator, and you began playing that role very early.

Since I’m old (relatively speaking: Finessi was born in 1966, ed.) I have had the good luck to come into contact with various masters. I began organizing situations to show their work because I realized that although they were giants, they were not always considered very important. Once I asked Munari why he never came to the Politecnico. “Because no one invites me,” he replied. It might have been a quip, but when I invited him to appear at the auditorium it was for a memorable lecture, with all the students wearing his “light-shield glasses” made of paper, with the inscription “I saw Bruno Munari at the Politecnico.” Twenty years ago, for two years, practically every day, I went to see Angelo Mangiarotti in his studio, and my dream was to do an exhibition on his work. Which eventually happened, at the Triennale, for his 80th birthday. When Munari died, the Salone – which in those years organized monographic exhibitions – asked me, by recommendation of Bruno Danese and Jacqueline Vodoz (the founders of the company Danese, ed.) to organize an exhibition about him, because we used to meet every Sunday at his house. A whole chain of things.

How did you first get interested in design?

It was immediate. My father had a small business, he made furniture, architects often came to our house and there was talk about décor culture. Then, as a kid, I began to learn about the works of certain designers I knew personally: Salvati and Tresoldi, for example. The first important encounter was with Munari. Then came other mentors: Corrado Levi, who supervised my thesis. Then Italo Lupi: one day, after graduating, I called the editorial offices of Abitare and asked for him, though I didn’t know him. They put him on the line and he invited me to go and see him. I obtained the possibility of writing an article for Abitare, and that was the start of a long collaboration, which came to an end when he stepped down as editor of the magazine.

What was your focus on the editorial staff?

I focused on something I have always done, since my youth: gathering material on everything that interested me and sorting it into folders. There was no Internet back then, they were real folders into which I put photocopies, magazine clippings, images. Each one became a sort of atlas for one idea, one concept. And I always looked for categories that were not necessarily established, unusual viewpoints. For Lupi, I proposed doing articles on these themes, these small inventories. Corrado Levi decided that these things should be called Bagatelles, which remained a code name the three of us utilized. With Italo I began to define the threads of the research: this led to the articles on clouds, or on order, and in time I developed the notion that these things could also become something else, besides being a part of Nautilus, the column Abitare printed on special moldmade paper inside the issue. When I left Abitare I began to think about a new object, and in the meantime I organized exhibitions and other things. Then I met Foscarini and the project Inventario was born (a bookzine on a variable schedule, ranging from half yearly to bi-yearly, founded in 2010, published by Corraini and sponsored by Foscarini). It is also made of many things I assign to my students: some of the articles, already in the first issue, were their degree theses. Articles about swings, the wind, the rain. Those first articles done with Italo made me think that these things could have their own value.

When Inventario won the Compasso d’Oro award – and few magazines have done so – what did that mean to you?

I received an email, I read it, and I couldn’t connect the two things, the magazine and the prize. Then we made some phone calls, with Foscarini and Corraini, and of course we were very happy indeed. We were in good company: Domus, Ottagono, L’Arca with the graphic design by Gianfranco Iliprandi. The part I liked best was the fact that we did it without following dictates of marketing, following our own preferences.

Are there any other projects in which you are particularly interested at the moment?

Of course, there are many. I would like to move forward with all the things I’m doing: something about my teacher, Corrado Levi, on which I’ve been working for some time now, and lots of other things.