Since its founding in 1990 by Piero Guicciardini, Marco Magni, and Nicola Capezzuoli, Florence studio Guicciardini & Magni Architetti has focused on cultural heritage concerning architecture, architectural restoration, and the design of exhibitions and interiors. Having designed over 60 museums and 80 temporary exhibits in Italy and abroad, Guicciardini & Magni has dealt with all kinds of installations – running the gamut from archeology, contemporary art, industrial design, classical art, and ethnography to fashion – applying a cross-functional design concept that focuses on both the objects and the changing needs of contemporary visitors. Often resulting from international competitions, their most important projects include the cathedral museums in Florence and Pisa, the Tekfur Palace and the Topkapi Palace museums in Istanbul, and the recently completed National Museum of Norway in Oslo and the Richelieu Library Galleries in Paris.

How has the concept of the museum changed in recent decades?

Throughout the 20th century, museums were places of “cultural awe” that could spark a feeling of unease, especially in children. Museums used to be places only visited by specialists and highly cultured people. But in the last few decades, they have taken on a major social role. Certainly, they have always represented national ambitions and identities, presenting themselves as signs or barometers of institutional power, but now they have become full-fledged social-cultural centers for their communities. We go to museums to learn but also to socialize, play, study, and develop ideas while having fun.

English and American institutions have greatly influenced this shift since they were the first to start focusing on visitors as well as the objects in their care. Even before World War II the British started paying attention to education, the world of children, teaching, and the role of the visitor, who may have been seen as a sort of “customer,” but at least one worthy of attention. Now visitors have become the real key players. The experience may be superficial because the level of general knowledge is sadly lacking, but the new public makes up a wide cross-section in terms of class and education. Now visitors have fun, are amused, and feel they have a right to do as they please since they no longer feel the unease I referred to.

How does this change translate when

it comes to design?

Visitor areas have become crucial. Museum entrances used to be just monumental, representational spaces, but now they are the key for interpreting the institution, the calling card for the entire undertaking. There is a more diverse public so now we involve specific groups of visitors, such as minorities and people with disabilities. Museums have become institutions with political power that often “comment” on outside events, movements, and behaviors.

Opera del Duomo Museum, Pisa, Italy

Opera del Duomo Museum, Pisa, Italy

We have tried to anticipate some of these trends. There were very few of us in the field of museography when we started in the early 1990s, but we were already trying to be open and inclusive, breaking architectural and cultural barriers, with our first designs for small ethnographic museums in Siena. Educational workshops have always played a big role in the museums we’ve worked on, making it clear how important children and school-aged visitors are.

When it comes to communicating, we figured out right away how important graphic design, lighting, and multimedia are for creating an engaging exhibition. As museographers and installation designers, we must understand how exhibitions can help people take on experiences, interests, and perceptions and turn them into individual experiences. We appreciate the potential of specific places and try to listen to their “inner voices,” combining curatorial needs with our interpretations of the values and stories borne by works and objects.

Opera del Duomo Museum, Florence, Italy

Opera del Duomo Museum, Florence, Italy

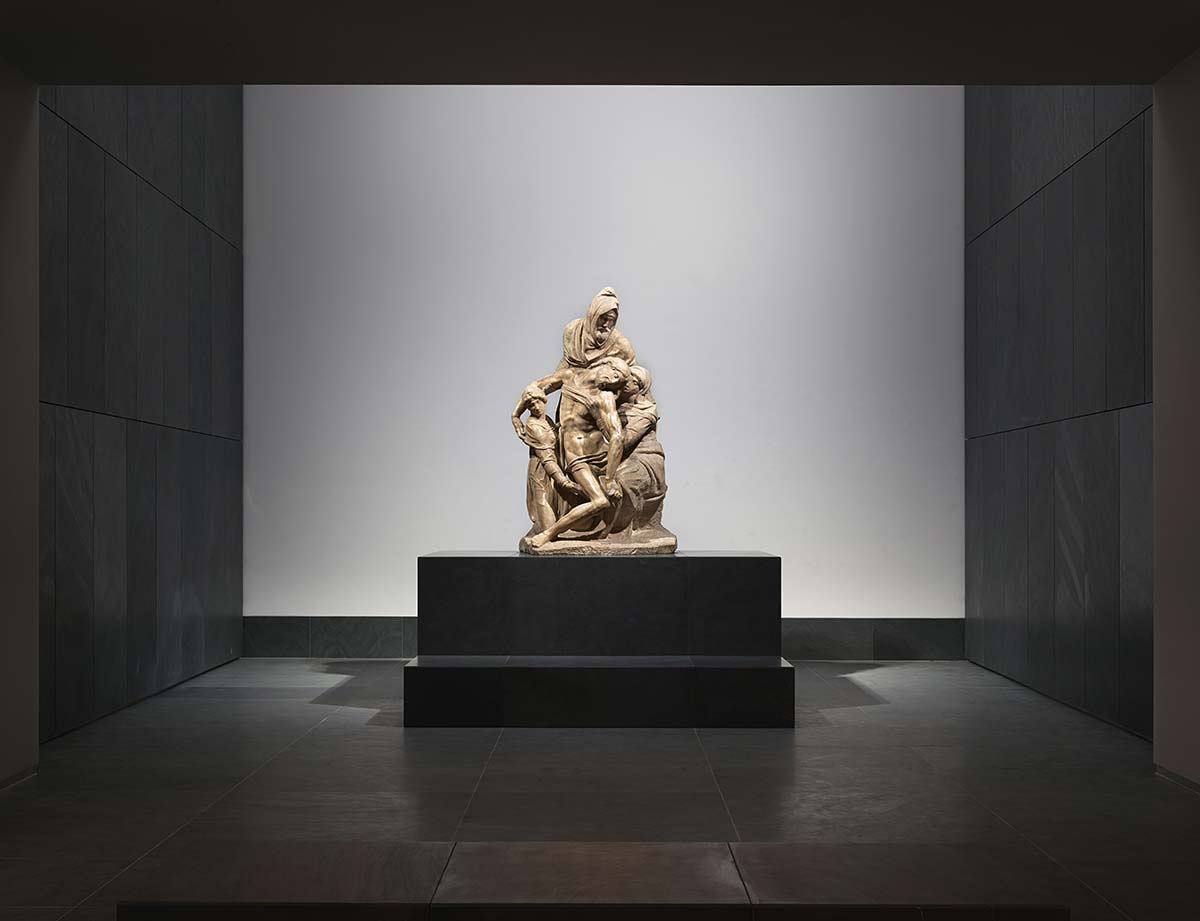

Often in Italy, less so abroad, we also deal with the architecture, which we consider vital having worked under master architect Adolfo Natalini. You can see this at Florence’s Opera del Duomo Museum where the architecture is central to the installation requirements. The Galleria del Campanile contains 16 marble-covered structures to hold Giotto’s 16 original sculptures for the bell tower, and the extraordinary space devoted to Arnolfo’s original cathedral façade was generated by the desire to create the reconstruction.

Which of your projects most convey a museum’s civic and political value?

A perfect example is the installation in Oslo’s National Museum. It is a grandiose museum that includes four different institutions and covers an area of over 50,000 square meters, 11,000 of which permanently display a wide variety of objects related to archeology, applied arts, design, art, and architecture within some 90 rooms. This powerful narrative spans history and its repercussions as seen by a country long perceived as “peripheral,” before Norwegian playwrights like Ibsen and artists like Edvard Munch began influencing the European cultural landscape in the late 19th century.

The National Museum, Oslo

The National Museum, Oslo

The Nasjonalmuseet tells these stories in a new, “fresh” way, thanks in part to the democratic way our group (which includes graphic design studio Rovai Weber, lighting technician Massimo Iarussi, and multimedia designer Alain Dupuy) interfaced for nearly five years with 17 different curatorial groups. We had some deeply respectful meetings in Oslo where ideas would emerge that I would often turn into sketches and then develop back in Florence in the weeks that followed. Fortunately the pandemic began when we were in the production phase and some of us did long stints in Norway supervising the work. In this case, the concepts of inclusiveness, openness, and generosity that we tried to interpret were part of the museum’s own mission.

How do you translate these concepts in practical terms, taking into account the short attention spans of today’s visitors?

Basically, by varying the spaces, lighting, and colors of the exhibitions. The Nasjonalmuseet’s 90 rooms are very similar in height, size, and materials given the architectural uniformity of Klaus Schuwerk’s design, so we were forced to invent installations that not only worked for the objects but also differentiated the spaces around them.

We designed some very distinctive installations and a line of benches with individual seats, games for kids, and multimedia and workstations. Visitors can interact variously both through multimedia and physically throughout the various rooms. The seats, display cases, and fittings were made by the Italian company Goppion using local materials like curved birch plywood and Norwegian wool to give the rooms a domestic, everyday feel.

The Richelieu Library, Paris

The Richelieu Library, Paris

At the Richelieu Library in Paris, on the other hand, the diversity and historical stratification of the rooms required a more placid, even-handed approach, which we expressed using precious materials of the courtly French decorative tradition like brass and bronze.

What are you working on now?

We recently installed a big show of classical sculpture at the Baths of Diocletian in Rome, “The Instant and Eternity,” sponsored by the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sport. We’re also working on some permanent installations for Pompeii, the Louvre, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where we’ve been shortlisted for the design of the Gilbert Galleries. Other projects involve the archaeological museums in Volterra, Florence, and Naples and the Caposanto in Pisa.

The Instant and Eternity exhibition – Baths of Diocletian, Rome

The Instant and Eternity exhibition – Baths of Diocletian, Rome

The Instant and Eternity exhibition – Baths of Diocletian, Rome

What are some of your other key reference points?

We value listening and being receptive because we’re aware that museums are collective organisms. While collections are formed by individuals, museums are formed by institutions and professionals who come together to create something new, at least in today’s museums. Our work is often compared, perhaps undeservedly, to that of the great Italian museographers.

But we have little to do with the approaches of Scarpa or Albini who focused on the idea of the cultured or elite visitor and an often poetic, value-laden presentation that required a considerable education to be understood. The Italian group we relate to most is BBPR, which started taking a social approach to museums and opening them to the masses in the 1960s and 1970s. They did it by working with graphic designers and artists, as they did for the Museum to Deportees in Carpi, tapping into the different professions that revolve around museums and becoming bearers of collective values.

Photo © Mario Ciampi

The Instant and Eternity exhibition – Baths of Diocletian, Rome