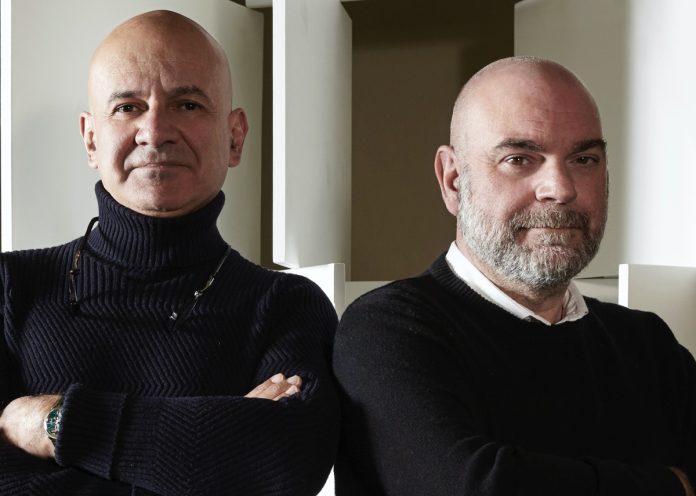

Behind initial appearances, Tiziano Vudafieri and Claudio Saverino unveil a world that moves against the common tide, a design credo that shifts with ease from History to Artificial Intelligence. Curiosity is the harmonious force that solves this non-conformist puzzle – because curiosity, as Vladimir Nabokov said – “is insubordination in its purest form.”

Meeting Vudafieri & Saverino is like running up against an infernal machine fed by dozens of disciplines, an assertive barrage of scene changes between music, art, literature, photography and history, recovery of the past and projection into the future, where architecture is a valuable final link. A duo of professionals who found each other without searching, demonstrating that “the other half of the apple” is history, not just mythology. The conversation with Tiziano Vudafieri (and in virtual terms with Claudio Saverino, who supplied precise written thoughts) runs fast, driven by passions and narratives, full of digressions that turn out to be essential for the final formulation.

Tiziano, you have had important “masters,” from Aldo Rossi to Ettore Sottsass. What have you inherited?

With Aldo Rossi, one of the great masters of 20th-century architecture, I completed my degree thesis at the School of Architecture of Venice. It was to some extent very close to his thinking, though not in an iconographic sense, and this aspect was particularly appreciated. A few months after graduation came the experience with Sottsass: I came from a small town in the Veneto, and in 1981 I landed in Milan. The impact with Sottsass was shocking, at first I didn’t understand, it was outside any aesthetic code to which I was accustomed, and I had also studied his work at the university. Then, finally, everything revealed itself, like The Great Beauty, but it took me months to get into tune and to understand his “what” and his “how.” In more than four years with Sottsass, I tried to get to the essence of the thinking of someone who in the second half of the 1900s (the first half was Gio Ponti) was the one who shuffled the cards. To summarize to the fullest, I say that from Aldo Rossi and Ettore Sottsass I inherited enormous, endless curiosity

Is there something in common between Tiziano and Claudio?

Claudio and I are very anti-disciplinary, we are not interested only in architecture and design: we are very attracted by art, because it is an ambit that challenges our idea of beauty. For example, I am fascinated by John Armleder, a Swiss artist who combines antique pieces with modern objects, also in outlandish interpretations. His eclecticism may not be immediately appealing, but when you grasp the concept it becomes irresistible. His works train you to see with different eyes, and above all to create fields of observation and thinking that are practically unlimited. A chair is a chair, but if it is made by an artist its primary function falls away, and that chair is no longer applied art but pure art, so you need to have a different approach to looking. This “looking with different eyes” is a process that can modify your parameters on beauty. If art is irritating that is a nice reaction, if it “smacks you in the fact” it is even better, because it puts you to the test. Art is an end in itself, in constant movement, so the same is true of beauty too.

Is Delvaux of Paris, with the due proportions, an example of transformation of an object into a work of art?

Definitely. Delvaux has a history (it is the oldest leather goods brand in the world, which began 25 years before Louis Vuitton) and incomparable know-how, quality of materials and workmanship. For the boutique on Rue Saint-Honoré we purchased French doors from Savoie from dealer in Cuneo; we hung them on the wall, with very light, minimalist shelves in front on which to display the handbags: the contrast works very nicely.

Vudafieri and Saverino: two very different backgrounds of education and work experience, combined in the current studio in 2000. What was the spark that set this off?

Claudio had come to work in the studio with me, there were six of us at the time. I immediately understood that he had what I was missing; we are equal and opposite, but perfectly complementary, based on mutual respect and lots of listening.

Reading the resumé of schooling and professional practice of Claudio Saverino, it seems like he wanted to do anything but be an architect.

That’s exactly right, but instead he is much more of an architect than I am, while I consider myself the only designer in the firm. Claudio comes from graphic design and communication, which have been passions and professional outlets for many years. Then he decided to change, to take a degree in architecture at the Milan Polytechnic under the guidance of Achille Castiglioni, with a thesis on the ancient city of Sousse in Tunisia, where he also investigates the Greek, Roman and Arabian origins of the Mediterranean house. The taste for exploration and discovery is still with him today.

One Delvaux deserves another, though different: is diversity an opportunity for a designer?

Absolutely, and it is also a compliment for us. Delvaux corresponds closely to our way of thinking, the relationship with Jean-Marc Loubier (CEO) has been very special. For every Delvaux we gather and interpret impressions on the personality of the site, mixed with the values of the company: in Tokyo we chose appliques by Frank Lloyd Wright utilized for the (unforgettable) Imperial Hotel, uniting them to form a large chandelier. In Paris we inserted original Savoyard doors, while in Rome we solarized Piranesi (not by chance, perhaps, one of the first Italian architectural theorists), moving him closer to Andy Warhol. In Milan we transformed a wardrobe by Portaluppi that was in Villa Necchi, making it match the style of Delvaux. Storytelling is essential, and in this sense Loubier, a great lover of design, is always a driving force.

What are your strong points?

We feel strong when there is a new story to tell, and when we can openly discuss things with the client: as Heraclitus said, “from opposition comes harmony.” We need confrontation, criticism, even aggression, if it serves to bring out the spirit of the investor: the machine kicks into gear, immediately.

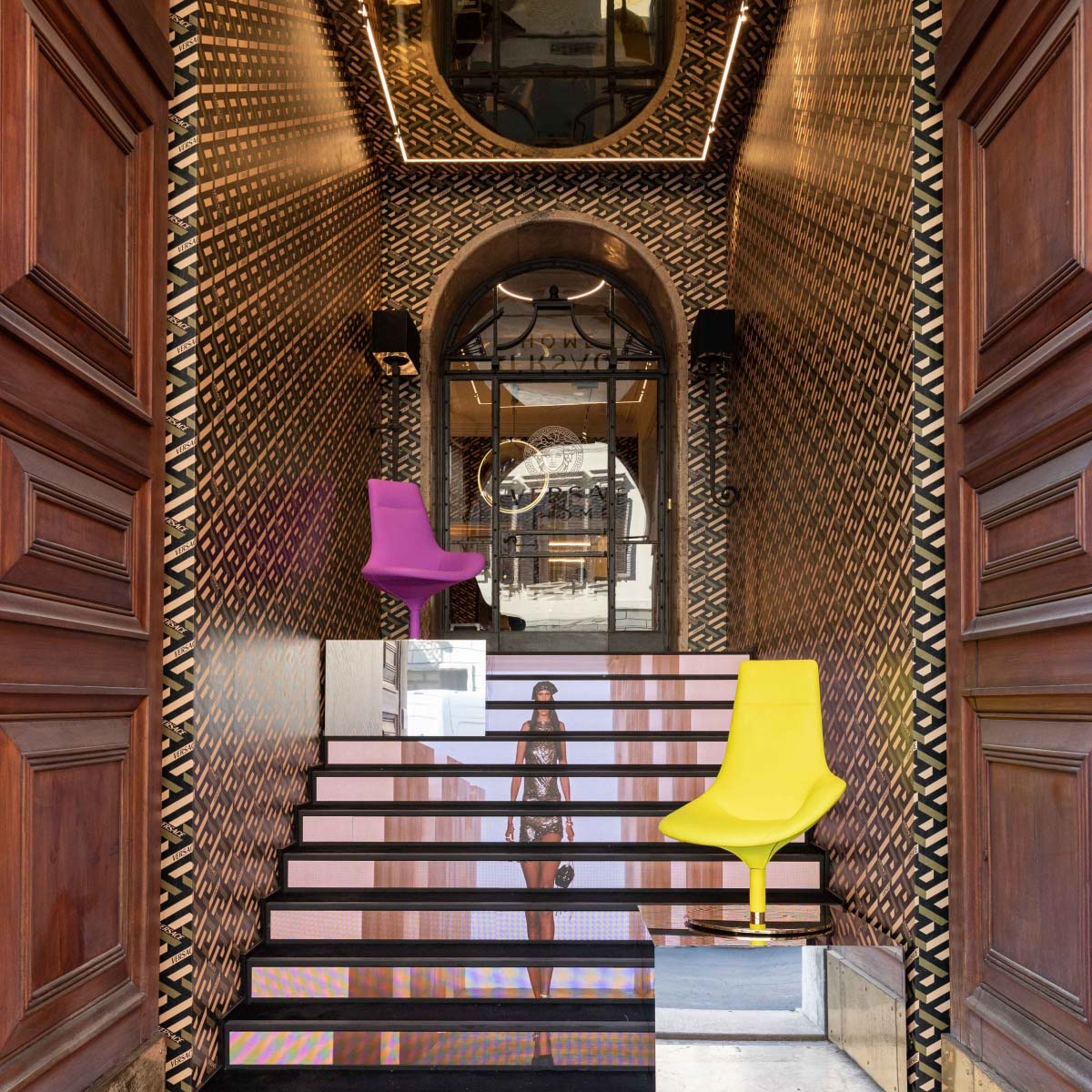

Versace Milano: do you think you have managed to “de-Versacify” Versace?

That was precisely our mission. The brief from Cassina asked us to make Versace less Versace, lowering the impact of the codes that have set the company apart for years (the Medusa, gold, etc). In the flagship store for Milan the distinctive symbols and forms of the brand have been reinterpreted through elements with an industrial tone, giving rise to a space with an eclectic character, in a dialogue between the classic architecture of the building and contemporary graftings.

In 2012, well before other international studios that decided to do the same, you opened an office in China.

It all began before 2012: intrigued by the ferment of the new Shanghai, for a visionary client we designed the headquarters of Wall Street English inside the Jin Mao Tower in Pudong, the tallest building in the world at the time. We were also working in the fashion sector. In that period it was complicated to be involved in fashion, China was very different, the passion for international brands had yet to explode, and we helped the companies to open stores. We did not have a company there, but we worked with a local architect. In 2012 we decided to form a company in Shanghai, and we were lucky to have an architect here in Milan who wanted to gain experience in China; he took the job, and discovered that China was the right place for him.

How has China changed over the last 11 years?

When we began working there, Italian designers and architects – and Europeans in general – were few. The country was beginning to open its doors to the world. Today, especially in Shanghai, the competition and the quality of the projects are comparable or better than in Milan, London or New York, so the clients too have evolved, becoming more demanding. They undoubtedly have a way of talking about projects that is different from ours: we westerners are used to working towards goals, along linear directions, while instead the Chinese do not proceed in a straight line, but on a rather winding path: they shift what you saw as the primary objective and jump ahead to topics you think are out of place for that moment. Nevertheless, they reach the goal, often before we do, and better. In the end, we have learned the flexibility of this path with the Chinese, and it permits us to get close to the objective even when a sudden change of direction arises.

A dream for the future?

We are very interested in the study of artificial intelligence. We have formed an in-house group oriented above all towards the opportunities connected with the production of images. We are studying Midjourney, a program that produces images by successive approximations, and if you understand the vocabulary and know how to ask the right questions (here a culture of humanism comes into play) it can bring clear results: in two hours, it produces what would previously have taken from two days to one week. For now we are practicing, but the group moves fast.