Buildings on which one appears to climb, houses uprooted and suspended in mid-air, lifts going nowhere, escalators tangled like threads in a ball of yarn, disorienting and surreal sculptures, and videos that subvert normality. These are all elements recounting something ordinary in an extraordinary context, in which everything is different from what it seems, and where we lose our sense of reality and perception of space. The exhibition ‘Leandro Erlich Oltre la soglia’ (Leandro Erlich Beyond the Threshold), staged at the Palazzo Reale last spring and curated by Francesco Stocchi, can be a good opportunity to extend the holiday effect, even if you have already returned to Milan. The exhibition, which has already won over millions of visitors worldwide – 600,000 in Tokyo and 300,000 in Buenos Aires – can still be visited in Milan until 4 October. The Milan exhibition gives visitors the opportunity to become better acquainted with Erlich’s art through his best-known and most iconic works, brought together for the first time in a single venue with the aim of systematizing the artist’s output.

An Argentine artist born in Buenos Aires in 1973, Leandro Erlich creates large installations with which the public relates and interacts, becoming the artwork itself. His work explores the perceptual bases of reality and our ability to question these same bases through a visual framework. The architecture of the everyday is a recurring theme in Erlich’s art, which aims to create a dialogue between what we believe and what we see, just as it seeks to bridge the gap between museum space and everyday experience. Each of Leandro Erlich’s works is to be read as a window onto the world that is sensitive to the gaze, that instead of misleading reveals the landscape that every person holds within his or her self. At first reaction, an Erlich work elicits a sense of familiarity with respect to the everyday, before raising a certain, insinuating doubt. By carefully gazing at the work, viewers begin to doubt what they perceive, as they are confronted with an inexplicable phenomenon.

“Erlich’s creations”, the exhibition’s curator Francesco Stocchi explains, “are architectural structures that function as optic machines that question the world’s sensory data.” The 19 exhibited works show that, by breaking free of the notions acquired with experience, each of us can experience a dimension of our own, a new, unblurred vision: the advent of a new kind of world. Each work is an event that regards small, everyday phenomena that, transferred to the museum space, acquire a new condition. The work stimulates new, collective behaviours and transforms automatic habits into moments of revelation, unease, and reorganization.

The exhibition itinerary already starts to surprise the visitor in Palazzo Reale’s courtyard, where the monumental site-specific installation Bâtiment, created in 2004 for Nuit Blanche in Paris, is set up. Since then, it has been presented worldwide, adapting to the characteristics of the local architecture. The exhibition mechanism, however, is always the same: the reproduction of a building façade, with balconies, niches, decorations, and awnings, is positioned horizontally on the ground. Visitors virtually “hang” from the decorations, while a large mirror, tilted at a 45° angle, reflects the ground image onto a vertical plane, giving the illusion of a real façade and the sensation that the law of gravity no longer exists.

Staircase (2005) looks like a natural-size spiral staircase, including the stairwell, and then rotated 90 degrees. Although the viewer is observing an artwork standing vertically from the floor, he or she is seized by the optical illusion of peeking down into a stairwell. The other people on the stairs can be seen looking from the side, and not up, which further reinforces an experience with unsettling features. With this work, which eliminates the role of a stairway to have people climb up and down, Erlich frees the architectural structure of its original function, transforming it, through its subversion of perception, into a stand-alone artwork.

Changing (2008). When the public enters the elegantly furnished changing room, it finds fulllength mirrors installed on three sides. But these mirrors extend into the distance, creating space rather than showing our reflection. You enter the changing room and discover it is connected to another one, which perhaps reflects your image with other mirrors. You might even encounter a stranger who suddenly appears in the mirror of a neighbouring changing room. Through this play of voids and illusions, the changing rooms proliferate like a maze outside the undefined boundaries. Confusion and the fear of getting lost dissolve to make way for the wonder of the encounter. Just like Alice who is lost through the looking-glass and no longer able to distinguish between one side of it and the other, between herself and the other, we are lost in a maze made of not one but no fewer than 30 changing rooms.

Although Hair Salon (2017) might look like a reconstruction of a hair salon with tidy chairs and mirrors, it holds surprises. Some mirrors do not show reflections as we are used to: we see not ourselves, but rather people who are not even present in the room, looking at us as disoriented as we are. And on the other side of what we think is the mirror is a completely different space. Erlich leverages our expectation that the mirror is showing us our face, while in reality the “mirror” is only a frame that separates another empty space, in a perceptive play of solids and voids that is common to the artist.

The Cloud (2018): one of the tendencies of humankind is to try to bring order and form to what is not there, as in the case of randomly arranged stars organized into constellations. Perceptive bewilderment and disorientation are constant features of Erlich’s work, which “has fun” creating images that unleash sensations of illusion in the viewer. Almost as if wishing to capture the impalpable, Erlich presents various clouds floating in imposing display cases like a cabinet of curiosities. In the same way, since Antiquity, we have imagined various shapes in clouds as they continuously change, undertaking a journey of dream through their constant mutations. Once outside, it comes naturally to raise our gaze and observe the sky which, according to the artist, with its lights, shapes, and colours, conditions the perception that each of us has of our city.

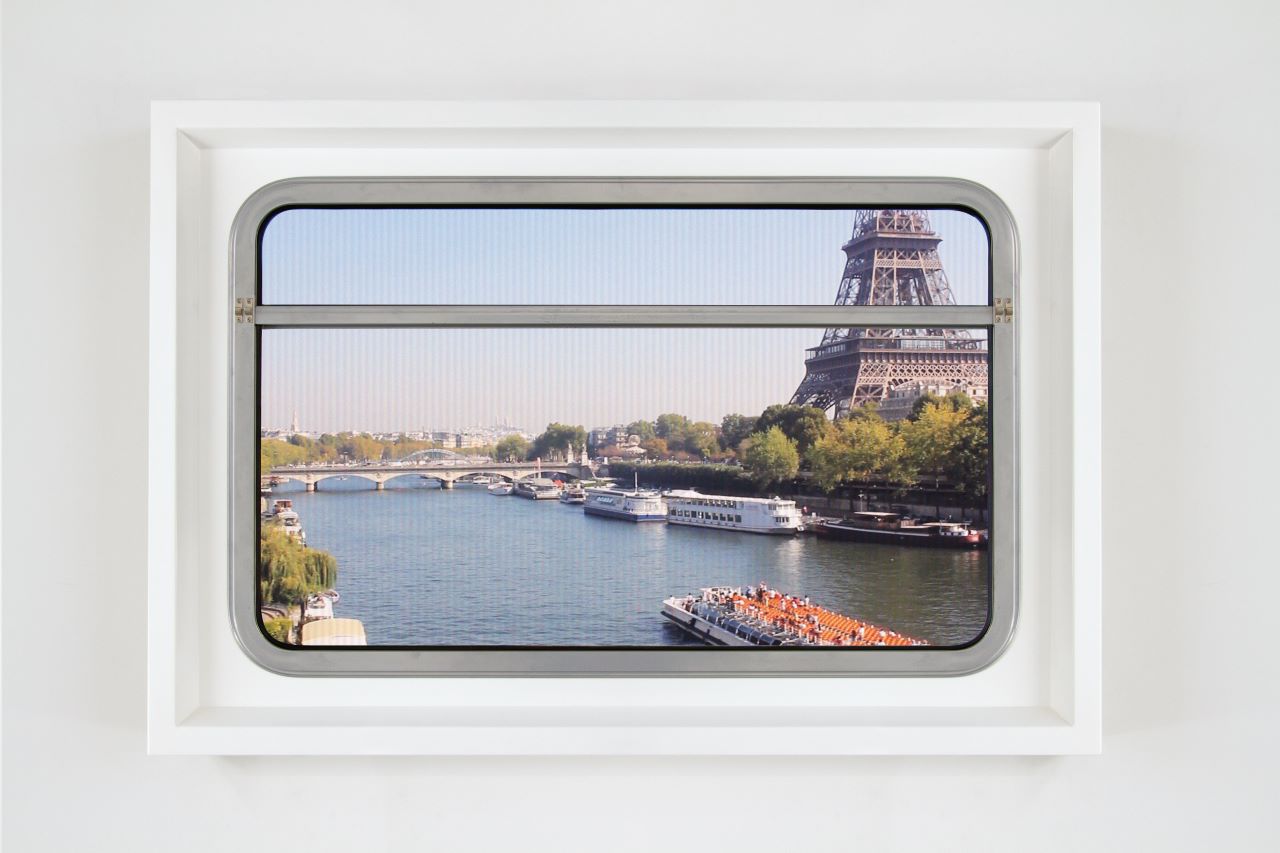

In Global Express (2011), urban landscapes pass by, outside of what appears to be the window of an elevated train or metro. As we observe the images, we can perceive the pressing rhythm of the journey, watching an iconic city (Tokyo) transform seamlessly into another (New York) and then yet another (Paris). Global Express reveals the monuments and architectural signs that we identify with each city. Entwined with them like a simultaneous event, we experience what technology offers us every day: the ability to traverse impossible distances in a matter of milliseconds. The architect of the uncertain, Leandro Erlich creates spaces with fluid and unstable boundaries. The video leaves us with the sensation of having made a unique journey, in which metropolises are fused into a single, global reel.

Rain (1999) was done for the first time on the occasion of the Whitney Biennial 2000 in New York, and ingeniously challenges the accepted convention according to which torrential rain can only take place outdoors. The work consists of a false exterior in the form of a staging made with a brick wall and windows, against which engineered raindrops are forcefully scattered, as lightning illuminates the sky. Beyond the disorientation characteristic of Erlich’s work, of seeing an exterior space from the interior, the piece generates strange and disturbing sensations of melancholy and fright, rooted in the condition of a rain that knows no interruption.