Andrea Maffei is an architect who has taken part in the architectural boom of recent years in Milan. With the gaze of someone who has intensely experienced Japan (where he worked with Arata Isozaki), the discipline and its paths of experimentation. Serious and courteous, his responses seem to whisper. And all the topics covered take him back to the essence of simple things: the vision of an architect, traveler, aesthete, but also a concrete practitioner.

A wandering architect: did you dream of that definition as a student?

After graduation, yes. I took a degree in Florence, where the opportunities for work were quite limited. In any case, the things being done abroad were more interesting that what was happening in Italy. CityLife and Porta Garibaldi/Varesine still did not exist, and the few developments in architecture (back in 1997) were works by Renzo Piano and Vittorio Gregotti. The explosion of projects was yet to come. I worked for a while in Pisa with Massimo Carmassi, where above all we concentrated on renovation of historical buildings. So I decided to go abroad. The most interesting destinations were America and Japan, and after various contacts I chose Japan and Arata Isozaki. It was an engaging experience, time passed quickly, and I stayed there for seven years. The rhythms of the work were very intense, also on Saturday and Sunday, we worked until midnight, and design competitions were many: a stadium with 80,000 seats designed in 15 days, for example.

Reading your biographical notes, we can see a clear preference for architecture. Is that the case?

Architecture clearly excites me more, and I think the time required to design an interior is equal to what is needed to design a building. I chose architecture, where I feel more at ease, I feel freer. It is a more consistent dimension than interior design, and I like the idea (if and when possible) of leaving a sign that belongs to the city, visible for all, fitting into the surrounding urban and social fabric.

The relationship with Arata Isozaki had a strong impact on your career: why did you decide to go to Japan and to work with him?

For a foreigner working in Japan is very difficult, mainly for reasons pertaining to language. They are reluctant to open their doors to a non-Japanese. Nevertheless, Isozaki (who reached the age of 91) was a very inclusive and hospitable architect, and the firm he constructed was the same, so I felt very comfortable with him and the whole staff. Isozaki always considered himself a citizen of the world, he also had an office in New York and he was always very interested in cultural contaminations.

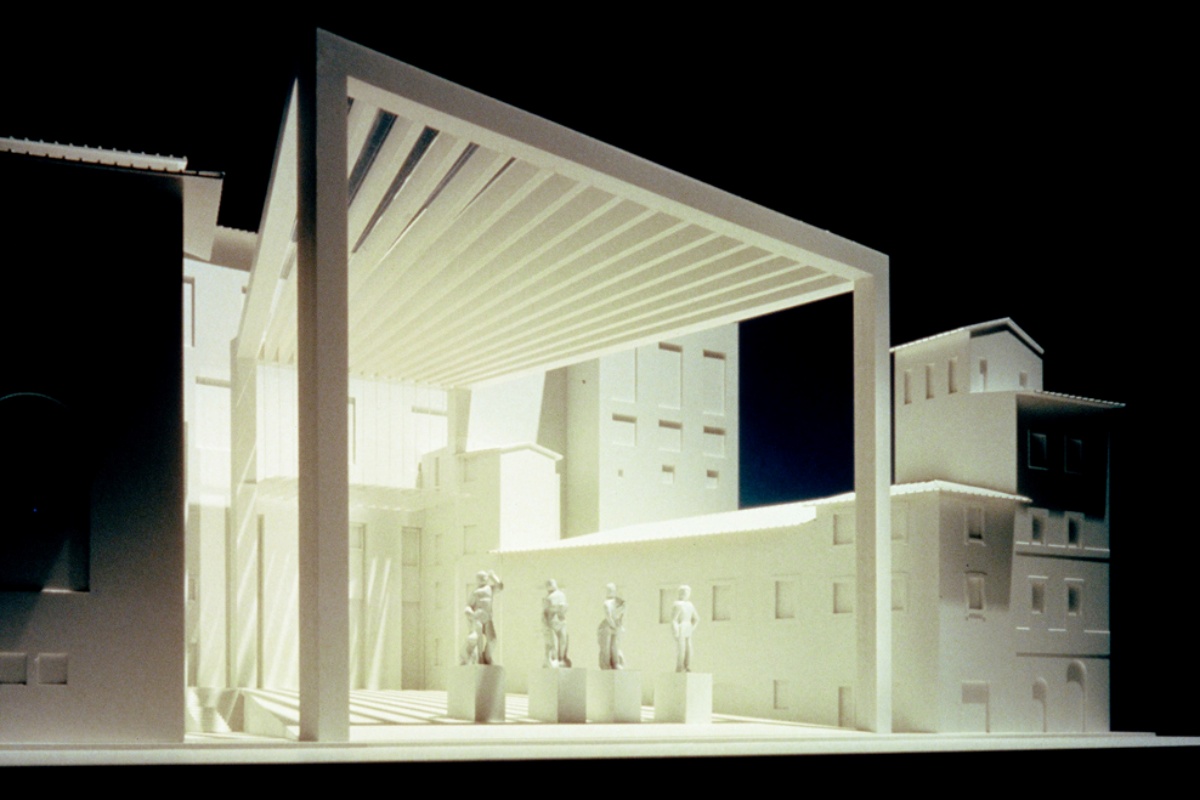

In 1998 his firm had won the competition for the Loggia of the Uffizi Museum in Florence, and Isozaki – I had just arrived – assigned me to the project. Then came projects in Qatar, where the most important works were the Museum of Islamic Art and a villa in the desert. Qatar was practically an unknown destination at the time, the airport of the capital was no larger than the airports of small tourism centers in Italy. Isozaki was an experimenter, he was not interested in developing a specific style to be replicated over time. He had been a student of Kenzo Tange and a great exponent of Japanese Metabolism, the movement that theorized the transformation of the cell into energy. In metaphorical terms, of course.

Do great works have to start with a dream?

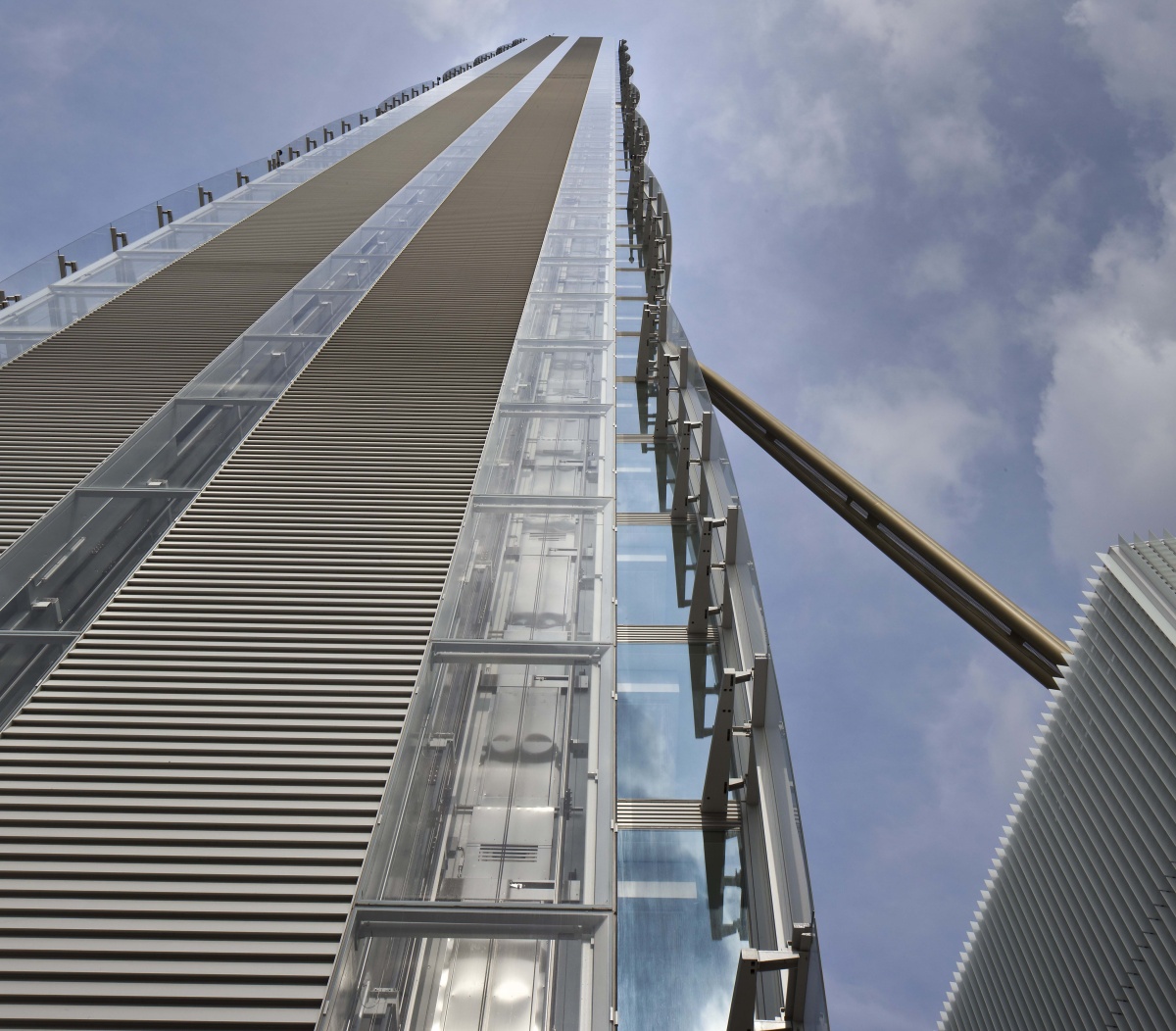

Absolutely. Without dreams, projects would always be the same. Without a specific narrative there would be no uniqueness, and architecture would serve only for its basic functions, without leaving an aesthetic mark. This is true of a museum, an office building or a residential complex.

If I were to choose one project from the many I’ve worked on, it would perhaps by the PalaHockey in Turin. We created a machine, also thinking about what would happen after the Olympics, so we imagined architecture that would be variable, capable of containing events of different kinds and sizes. A big box where the stands can be moved for different situations. We called it “a big machine for events.” And the inspiration came from what Kenzo Tange designed for the Osaka Expo in 1970.

What do you think about the relationship between your job and sustainability?

Sustainability can no longer be an optional, it is a fundamental parameter that determines the grammar of the design. And the demand for serious sustainability comes not only from owners, but also from developers, who assign major commercial value to the level of eco-compatibility and the related certifications.

A dream for the future?

To design a museum! Museums are fascinating places, where culture lives and passes through. Every museum is different from the others. I would love to design one.