Deyan Sudjic is, above all, a man of culture: his reading of architecture and design is very often linked to annotations on the society that produced those works. And his observations often suggest new keys to interpretation. We met him (via Zoom) and the conversation immediately broadened from design to the world situation, passing through considerations on modernity.

First question: what is design?

There’s always been a slight schizophrenia for me. Design to me emerges at that moment in the past when the connection between craft and the user was broken by mass production. Earlier relationships were very direct. Those could afford it would have a chair made for them by a craftsman in the same way that they might have a pair of shoes made for them. Machines cut that connection. They made things more affordable, more democratic. But there’s no longer that personal relationship. And this is when the contemporary professional design is born. And in some ways that can be seen as a progressive thing. In others, if you believe in William Morris, it actually makes labor less dignified. And it also introduces these two different versions of what design can be. One version is that sense of manufacturing want and desire. That sense of how does a manufacturer give a mass produced object value or price? How can it manufacture desire, which is the kind of cynical, manipulative understanding of what design can be. And the other one has always been that sense of, however naively, seeing design as a way to make the world a better place, a tool by which people can address real needs. One can say the tension between William Morris and Philippe Starck.

Where are we now?

We’re in a period in which the object is no longer so powerful as it once was. A post analog age in which working with the digital is something that design has to engage with. Those old certainties about design making the world a better place feel less certain. The Bauhaus believed that if you interpret needs correctly, then you’ll make an object that is as perfect as you can make it. Now there’s a sense that if you actually can try and make something carbon neutral, then that is the imperative. Italy is still a place in which, for the time being, there is a direct connection between design skills and manufacturing, which for a certain kind of design is very important. Europe has probably lost the ability to do very much in the digital world. Silicon chips are made in China or Taiwan. Smartphones are made in a gigantic factory in the center of China. The old world of Olivetti, Brion, Siemens or Braun are all gone and dissipated. And so it becomes harder and harder for design in Europe to have much to offer to those territories.

Where do you think design is going?

There are two things that will manifest themselves in Milan in June which to me sounds interesting. And maybe they’re opposite ends of the spectrum. George Sowden, who a long time ago was actually an Olivetti designer together with Ettore Sottsass, in the last ten years is becoming his own client, using the global supply chain to make products that he designs and markets himself. He will be opening Spazio Quarantaquattro, in corso di Porta Nuova, in which he will actually show some of the fruits of that. He’s not te only one. On the other hand, I find it really intriguing how that Memphis explosion from 1981 will not go away. The Memphis brand now belongs to the same company that owns Gufram, and they are taking over a floor in the Triennale to show 200 Memphis objects in an exhibition. Two small ideas: one is that sense of how particular moments in history will not go away, and the other is of how the designer – less and less relevant in the era of the giant company – can take command of the process. In the era of the giant company the role of the independent outside design consultant, whether it’s in Tesla or in the Metaverse or in Apple, has become more and more fragile.

Does an operation like that of Sowden make a designer closer to the figure of the artist?

I don’t think so. Sowden and the others doing are not making one offs or editions. They are just going to the source of the factories in mainland China, those that can produce thousands of coffee pots or hundreds of jugs. These are not usually technically very ambitious, but these objects can actually still have meaning.

What do you think is modern today?

Well, the word modern goes back to at least the 18th century, and people find it quite hard to say that they are not modern. However, I must say that the world is not looking a particularly attractive place at the moment, and we’re kind of seeing all kinds of premodern manifestations. There’s something really eerie about a world in which Vladimir Putin can call upon the ghosts of ancient Slavdom – and I speak as a Slav – myself to try and justify the invasion of another country. The symbolism is so strange that Putin’s Army, on its so called special military operation, is blessed by the primate of the Russian Orthodox Church wearing the outfit of the Middle Ages. And at the same time in the occupied territories in Ukraine, apparently they’re reinstalling statues of Lenin and Soviet era flags. What a strange mixture of iconography is that? And one could say this is the ultimate expression of post modernity. Two years ago we were struggling with the idea of a pandemic. It actually made me think about how the first modernity in architecture was born: from hygiene.

Can cities change history? And can objects change people?

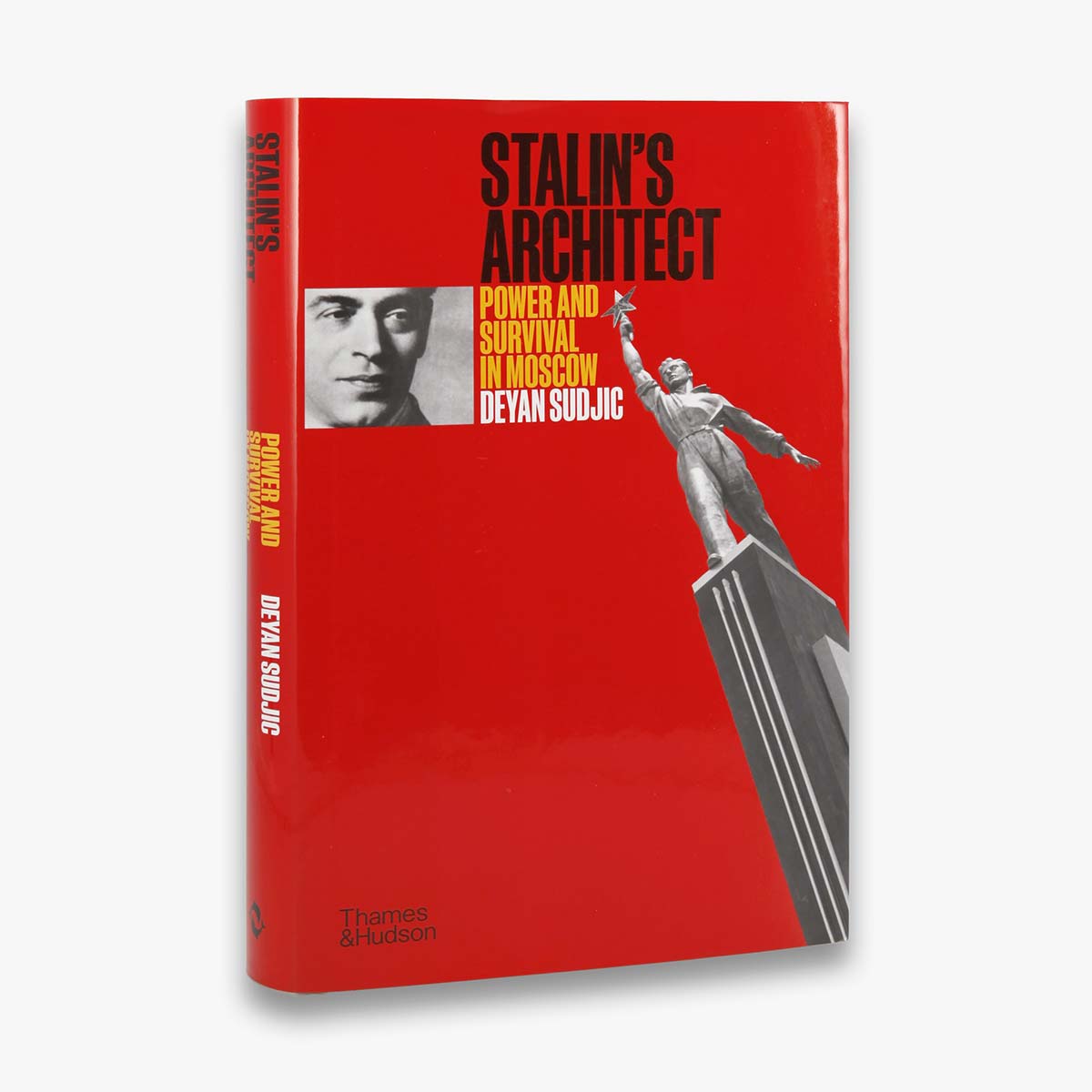

They certainly can. And they do, yes. In history, the city has been a focus in which people can resist nationalism. Stalin’s architect (the newst book by Sudjic is Stalin’s Architect – Power and Survival in Moscow, Thames & Hudson – Ediotr’s note) was actually born in Odessa, a city that was built when the Russian Empire took over what was then an Ottoman fortress. In its early years, Odessa was more like Shanghai or Hong Kong. The administration was subcontracted. They built an opera house before a Russian Orthodox Church. The art school was started by an Italian architect. So this was actually a very cultural, dynamic place. And that’s the kind of cities that makes a difference to me. Can objects change lives? Of course they can. Just think about the consequences of the smartphone. When Jobs and Jony Ive launched the first iPhone, even they could not have foreseen that it will actually change the dynamics of American elections, that it would change the ways in which we relate to each other in terms of meeting each other. And that it would actually lead to the abolition of so many different kinds of products and objects.